Agricultural & Farming Accounting

Accounting & Bookkeeping for Agricultural & Farming Businesses in Canada

Introduction

In most respects an agricultural business is very much like any others: goods and services are purchased; these are processed, consumed or resold; revenue is earned from selling goods and, to a lesser extent, services.

There are several features of agricultural businesses that are rather different than most, however. Many of these relate to the way in which agricultural businesses are allowed to account for operations for income tax purposes.

In this article we will review some of the unique features that are relevant in accounting for an agricultural business.

Much of what follows deals with how to account for agricultural operations in order to produce a net income number that will be useful for income tax reporting. For many agricultural businesses most of the accounting is designed to produce an accurate income tax number.

Setting Up the Accounts

As with any other business, the accounts for an agricultural business should reflect the underlying nature of the transactions it enters into. Thus, revenue accounts might distinguish grain sales, identifying separately wheat, oats, barley, etc., livestock sales, poultry and whatever other categories of commodity the business produces and sells. Separate revenue accounts will be required for government support payments if the farming business qualifies for them.

As with any other business, the accounts for an agricultural business should reflect the underlying nature of the transactions it enters into. Thus, revenue accounts might distinguish grain sales, identifying separately wheat, oats, barley, etc., livestock sales, poultry and whatever other categories of commodity the business produces and sells. Separate revenue accounts will be required for government support payments if the farming business qualifies for them.

Similarly, expense accounts will reflect the nature of the related business inputs – fertilizer, fuel, casual labour, contract services (such as spraying, combining), etc.

The major distinguishing factor for agricultural businesses in Canada is, however, that farming and fishing businesses are the only businesses which are allowed to use a form of cash-basis accounting in reporting income for income tax purposes.

Because cash-basis accounts are generally simpler to prepare than accrual accounts, a farming or fishing business that chooses to use cash-basis accounting for income tax reporting will often set up its records on a cash basis from the outset, rather than setting up accrual accounts and adjusting them to a cash basis.

Cash vs Accrual Accounting

The starting point is to understand how cash and accrual accounting differ.

Cash-basis accounting recognizes revenue when the cash is received and expenses when they are paid; accrual accounting recognizes revenue when it is earned and expenses when the related liability arises. Cash basis accounts still distinguish capital from operating expenses, though, so that capital outlays are not deducted when incurred but capitalized and amortized.

Thus, the major differences one would anticipate encountering between the two is that accrual accounts include accounts receivable, accounts payable, prepaid expenses and deferred (unearned) revenue; cash-basis accounts do not.

Canadian income tax law requires that most taxpayers report their operations for income tax purposes using accrual accounting, with a limited exception made for taxpayers reporting business income from farming and fishing as mentioned above.

Despite the fact that it produces an arbitrary measure of income, cash-basis accounting is very commonly used in the real world. Its most general use is for the day-to-day entry of transactions and the simple summarization of those transactions for a particular reporting period (month, fiscal quarter or year). Having entered and summarized the cash-basis transactions for the year, the bookkeeper finds that it is relatively straightforward to quantify, record and post the adjustments required to convert the cash-basis accounts to full accrual accounting, and from these accounts to produce the balance sheet, income statement and other financial reports.

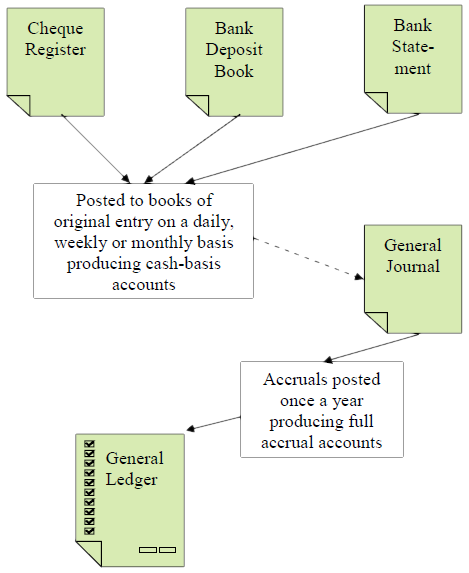

In other words, it is common that the books of original entry are maintained on a cash basis and that full accrual accounts are only prepared when financial statements are required. This transaction flow can be summarized as follows, assuming that the business enterprise produces full accrual financial statements only once a year:.

.

This system for maintaining the books of original entry is extremely common in small enterprises, particularly those that use a contract bookkeeper to prepare one set of full accrual accounts once a year – typically to produce the financial statements for use in preparing the income tax return.

In a typical situation:

Once a year, the bookkeeper’s client will bring the bank deposit book, the cheque register or stubs and the bank statements for the year. The bookkeeper will enter these in the accounting records on a cash basis. These accounting records may be maintained electronically (a spreadsheet program, such as Excel) or by using a fully computerized accounting system. However, many fully computerized accounting systems are not set up to accommodate the entry of cash-basis transactions, in which case the bookkeeper may post all the transactions for the year, as summarized from the manual or spreadsheet work papers, as one journal entry into the computerized accounting system.

Using additional information provided by the client, the bookkeeper will quantify accounts receivable, accounts payable, prepaid expenses, deferred revenue and any other cash-to-accrual adjustments, and record them as journal entries. (If the accounts are to be prepared on a cash basis, these adjustments are ignored.)

The accrual basis accounts are then used to prepare financial statements.

Cash Accounting for Income Tax Purposes

If a farming or fishing business elects to use cash-basis accounting for income tax purposes, the adjustments to convert cash accounts to an accrual basis described above are unnecessary. However, there are adjustments which are required to cash-basis accounts when a farming or fishing business reports this way for income tax purposes because income tax cash accounting is not true cash accounting.

Prepaid Expenses

A special rule applies to farmers or fishers who prepay expenses. If the prepaid expenditure relates to a period more than one year from the end of the current taxation year, that portion of the cost is not deductible on a cash basis and can only be deducted in a year that is within one year of the period to which it relates.

Land Clearing Costs

A special rule permits a farmer to deduct the cost of clearing or levelling land or installing a drainage system. Such costs would otherwise be capital costs, to be added to the cost base of the land.

Inventories

In line with normal cash-basis accounting, the cost of inventories is deducted as the inventories are paid for.

However, in a year in which a farmer (but not a fisher) has a loss from farming, an adjustment to the loss may be required if the farmer has inventory on hand. The nature of the adjustment varies depending on whether the inventory was purchased (purchased livestock, seed grains, fertilizer, fuel, etc.) or if the inventory represents a certain type of livestock. Furthermore, a farmer with inventory on hand at year end, whether purchased on not, may elect to take some or all its value into income if that is to the farmer’s advantage.

Where inventory must be valued in order to apply these rules, there are specific limitations on how it is to be valued.

Purchased Inventory –The Mandatory Inventory Adjustment

If a farmer (but not a fisher) has a loss for the year computed using cash basis accounting and also has purchased inventory on hand at the end of the year, the loss must be reduced by the lesser of the amount of the loss and the value of the inventory.

For these purposes, purchased inventory must be valued at the lower of cost and fair market value. However, if the purchased inventory is a horse or a bovine animal with a registered pedigree, it can be valued at any amount not exceeding its cash cost and not less than 70% of the total of the amount at which it was valued in the prior year, plus any additional cash amounts paid for it in the year.

An amount taken into income as a mandatory inventory adjustment in one year is deducted in the next.

Example - Mandatory Inventory Adjustment

Joelle operates a poultry farm. At the end of 2015, her cash basis accounts, after claiming capital cost allowance, show a loss of $15,000. At the end of 2015 Joelle’s inventory consisted of $11,200 of feed for her chickens and $45,000 worth of chickens, all of which she had raised from hatchlings. Joelle’s mandatory inventory adjustment is the lesser of her loss ($15,000) and the value of her purchased inventory ($11,200). She must therefore add $11,200 to her 2015 income and she will deduct the same amount in 2016.

Optional Inventory Adjustment

A farmer is also permitted to record an optional inventory adjustment even where the mandatory adjustment is not required or has been applied to reduce or eliminate a cash loss. The optional inventory adjustment allows the farmer (but not a fisher) to take into income the value of any inventory on hand, which will include both purchased inventory and inventory that has been produced – grain grown, cattle raised.

Again, the optional inventory adjustment taken into income in one year is deducted in the next.

The optional inventory adjustment is a very useful tool to be used by a farmer to average his or her income over a period of years. Like all other taxpayers, farmers can also manage their income by claiming less than the maximum capital cost allowance that is available.

Example - Optional Inventory Adjustment

Cameron operates a grain farm. For 2015, his cash-basis accounts show a profit of $15,000, after capital cost allowance. Cameron has $175,000 of wheat and oats in his bins that he has not yet sold. Cameron can add any amount, up to $175,000, to his 2015 income. He chooses to add $85,000, bringing his income up to $100,000 for the year, in order to be able to deduct RRSP contributions he has carried forward and to utilize the full personal credits he has available. Cameron will deduct $85,000 in computing his net income in 2016.

Farm Quotas

A payment to acquire a farm quota is an eligible capital expenditure and is not deductible as incurred.

The Basic Herd

A bookkeeper will occasionally encounter a farmer or, more likely, someone who thinks they know something about farming who will mention the concept of a ‘basic herd’. Although the rules governing basic herds are still in the Income Tax Act, they only apply to livestock that was on hand at the end of 1972.

The CRA no longer publishes information relating to basic herds and it is unlikely in the extreme that any farmer still has an animal in inventory that was part of a basic herd.

Summary

A farmer who has elected to report farming operations on a cash basis will generally, then, keep his or her farming records on a cash basis. For income tax purposes, this cash basis income or loss is adjusted in calculating net income for income tax purposes as follows:

Adjust the cash basis income or loss to add back the claim for any expenses prepaid which relate to a period after the end of the following year.

Claim capital cost allowance and the amortization of eligible capital expenditures (which are not cash expenses). These claims can be less than the maximum available if income is being managed.

If the cash statements so adjusted show a loss, reduce the loss by the mandatory inventory adjustment to the extent there is purchased inventory on hand.

If the farmer wishes, book the optional inventory adjustment if there is inventory on hand of any kind.

These adjustments are tax adjustments only and are typically recorded only on the income tax return and not in the books of the farm business.

Personal Use Expenditures

It is not uncommon for a farmer to be required to allocate expenditures that relate to the farming business but which also have a personal-use component. The portion of the expenditure that relates to personal use is clearly not part of the business and should be excluded from the determination of farming income.

Examples of such expenditures include:

Property taxes – property taxes that relate to the homestead are not a business expense; those that relate to the balance of the farm are.

Inventory consumed – costs that relate to the production of inventory that could have been sold, such as eggs, meat and milk, but which was consumed personally should not be deducted.

Motor vehicle costs – if one or more motor vehicles are used both personally and for earning farm income, the operating costs of the vehicle must be prorated. The most direct way to do this is to prorate based on kilometers driven, distinguishing those that relate to business activities and those that are personal.

It is highly advisable that a farmer who uses vehicles in this way maintain a mileage log to support the allocation of costs between business and personal use. The issue becomes acute if the CRA audits the business income statement as part of an income tax audit. Absent a log produced at the time the vehicle was driven the CRA will normally reassess to allow only a portion of the costs claimed, based on some more-or-less arbitrary measure that the Agency comes up with.

Personal Residence – normally a farmer would not include any portion of the cost of his or her personal residence as an expenditure that relates to the business. However, it is likely that some occupancy costs – telephone charges, internet – have both a business and personal component, and should be prorated.

- In addition, a portion of the home may be used exclusively for business purposes – to maintain a farm office, or as a residence for farm hands, for example. Where this is the case, a portion of the operating costs of the home can be allocated to and claimed in computing farm income.

Farm Losses

It is important to understand the differences between the three types of loss described below. While the Income Tax Act refers to “farm losses” and “restricted farm losses”, it also provides that for these purposes farming includes a fishing enterprise, so that these rules apply equally to farmers and fishers.

Fully Deductible Farm Losses

If farming is the chief source of income, and it can be demonstrated that the farm is being run with a reasonable expectation of profit as a viable enterprise on a commercially rational basis, any farm loss is fully deductible against other sources of income.

Restricted Farm Losses

If farming is not the chief source of the taxpayer’s income, but the activity is carried on with a reasonable expectation of profit, any farm loss is limited to the total of 100% of the first $2,500 of loss and 50% of any remaining farm loss, to a maximum of $17,500. This allowable portion of a restricted farm loss can be offset against any other sources of income.

If the actual farm loss is greater than the allowable deduction, the excess may be carried back three years or forward twenty years to offset only net farm income realized in those years.

Unused Restricted Farm Losses

Where a farm business is sold when unused restricted farm losses are still being carried forward, part of these unused restricted farm losses may be used to increase the adjusted cost base of the land and thereby to reduce any capital gain on farmland sold. The capital gain may be reduced by the amount of the property taxes and interest on borrowed funds used to buy the land that were included in the restricted farm loss.

Example - Restricted Farm Loss

Susan is building up her berry farming operation. In the first few years, however, she has been working full time in town as a nurse. Last year, she was employed full-time and also grew, harvested, and sold a crop of Saskatoon berries. Because of a poor crop, however, Susan had a farm loss of $10,000. Susan will fall under the Restricted Farm Loss rules because farming was not her chief source of income last year. The loss she may deduct will be limited to $6,250 ($2,500 plus 50% of ($10,000 - $2,500)). The rest of the loss, $3,750, that can’t be claimed in that year can be carried back to offset net farm income in the prior 3 years, or can be carried forward for 20 years to offset future net farm income.

Establishing the Chief Source of Income

Farming will generally not be considered the chief source of income if the taxpayer has a full-time occupation other than farming. For example, a farmer who works as a school teacher during the year would generally be considered not to be in the business of farming as the chief source of income.

However, CRA considers a number of factors, not just revenue amounts or sources, when deciding whether farming is the chief source of income. These include:

- gross and net income of the farming operation,

- the amount of capital invested,

- the size of property used in the farming operation. If the farm is too small to project any hope of profit, if no attempt has been made to develop or farm the land or if there is no intention to use more than a small fraction of the land over time to produce income, the operation may be classified part-time (or even as a hobby as discussed below),

- the potential for profit as supported by cash flow statements and budgets for the future,

- the time spent farming, especially in the busy harvest months in the case of seasonal enterprises,

- the background and experience in farming and level of personal involvement in the operations,

- eligibility for provincial assistance, and

- other income sources.

Hobby Farm Losses

If a farming operation is found to run for personal enjoyment rather than as a business with a potential for profit, any loss incurred will not be deductible at all. For example, someone who owns several acres of land and keeps horses for riding would be generally considered a hobby farmer. Like any other undertaking, if there is a personal component and no reasonable expectation of profit from the business then losses are not deductible.

SPECIAL FARMING ISSUES

Feedlot Operators

The CRA has had to develop an administrative policy to deal with feedlot operators, in order to assess whether these should be viewed as being engaged in the business of farming or not.

This policy was outlined in an Interpretation Bulletin which has subsequently been archived by the CRA, which means that it may no longer represent policy. However, as it has not been replaced by a new policy, it appears to reflect the current assessing practice.

A feedlot is considered to be a farming business if it makes an ‘appreciable contribution’ to the raising of the livestock, taken by the CRA to mean that:

- animals are on the lot for an average of at least 60 days; or

- the average weight gain of animals on the lot is at least 200 lbs.

If these conditions are not met the feedlot is not a farm but simply a regular business and the cash basis of accounting cannot be used.

Woodlot Operators

Similarly, administrative criteria have been developed in assessing whether a woodlot is a farm.

As a preliminary step, the CRA distinguishes a commercial woodlot from a non-commercial woodlot. A commercial woodlot is one operated with a reasonable expectation of profit and therefore as a business. A non-commercial woodlot is not so operated and would encompass, for example, idle land on which trees are grown but not harvested or marketed commercially.

Only a commercial woodlot can be treated as a farm. The CRA’s view is that where the focus in the operation of the woodlot is the cultivation of trees and not their harvesting the woodlot will be treated as a farm.

Government Support Programs

Virtually every country in the developed world provides income support payments to its agricultural industries. In some cases, the support payments are so generous that they lead to substantial overproduction of the subsidized goods which substantially distorts world markets and renders it uneconomic to produce goods in developing countries, which cannot afford subsidies.

It is not possible here to inventory every program that is available. Some are targeted at particular sectors; some at particular activities; some are provided by provincial governments. However, the most commonly encountered programs in the agricultural sector today are AgriStability and AgriInvest (replacing ‘CAIS’ – the Canadian Agricultural Income Stabilization program for the 2007 program year), and the various crop insurance programs that are available.

AgriStability and AgriInvest

The main features of AgriStability include:

- You receive an AgriStability payment when your current year program margin falls below 85% of your reference margin. AgriStability is based on margins:

- Program margin - your allowable income minus your allowable expenses in a given year, with adjustments for changes in receivables, payables and inventory. These adjustments are made based on information you submit on the AgriStability harmonized form.

- Reference margin - your average program margin for three of the past five years (the lowest and highest margins are dropped from the calculation).

- Should your production margin fall below 85% of your reference margin in a given year, you will receive a program payment.

The main features of AgriInvest include:

- AgriInvest accounts help producers protect their margin from small declines. AgriInvest replaces the coverage for margin declines of less than 15%, previously covered by the Canadian Agricultural Income Stabilization (CAIS) program.

- Each year, producers will make a deposit into an AgriInvest account, and receive a matching contribution from federal and provincial governments.

- Producers will have the flexibility to use the funds to cover small margin declines or for risk mitigation and other investments.

Crop Insurance

Most provincial governments run a variety of crop insurance programs. These provide insurance against various natural catastrophes and normally require that a farmer pay an insurance premium in order to participate. Crop insurance premiums paid are a deductible expense and insurance payments received are taxable.

Sales Taxes and the Agricultural Sector

GST/HST

A more detailed description of how the GST generally applies is included in our Accounting News article “Sales Taxes in Canada”.

Most agricultural products are zero-rated, meaning that the farmer or fisher does not collect GST on revenues earned but recovers all of the GST paid on inputs.

Many inputs that are targeted specifically at the agricultural sector are themselves zero-rated. GST registrants engaged in agriculture are typically in a GST refund position and would therefore normally choose to file as frequently as possible.

Special rules apply to the supply of farmland, whether it is sold or rented. Generally, such a supply is taxable unless the farmland is ceasing to be farmed and is transferring to the farmer personally or someone related to the farmer.

Retail Sales Taxes

The provinces which impose retail sales taxes often have special rules for those in the agricultural sector. Generally, these rules will relieve a farmer from paying retail sales tax on goods that would normally be taxable where the goods are acquired for farm use. Our Accounting News article “Sales Taxes in Canada” provides links to the provincial tax sites.

SUMMARY

Farmers and fishers are permitted to report business operations for income tax purposes using a modified form of cash-basis accounting. The activities of such businesses are therefore generally recorded on a cash basis.

There are, however, certain adjustments to cash-basis accounts which are required for income tax purposes.

Special rules relate to the allocation of expenditures which have a personal-use component, the acquisition of a quota, the deduction of farming losses against income from other sources and the treatment of feedlot and woodlot operators.

Many farmers participate in AgriStability and AgriInvest, income support programs which require that additional accounting information be provided to the regulatory authorities.

The agricultural sector is generally zero-rated under the GST.

We can assist you with advice and reporting as it relates to Agricultural & Farming business issues such as cash versus accrual accounting and farming inventory in Canada. Here at Green Quarter Consulting - Accounting and Bookkeeping Services for Small Businesses in White Rock South Surrey, Vancouver, Langley and Surrey BC, we assist Small Business Owners with analyzing transactions, sources of income and your tax risks and how they relate to your business strategy. Learn more about our Greenstamp CFO Services here.

We can assist you with advice and reporting as it relates to Agricultural & Farming business issues such as cash versus accrual accounting and farming inventory in Canada. Here at Green Quarter Consulting - Accounting and Bookkeeping Services for Small Businesses in White Rock South Surrey, Vancouver, Langley and Surrey BC, we assist Small Business Owners with analyzing transactions, sources of income and your tax risks and how they relate to your business strategy. Learn more about our Greenstamp CFO Services here.

Contact us today at 778-791-2864 or 604-970-0658, let’s talk, or send us an email here and we will be in touch very shortly.

GET YOUR FREE CONSULTATION TODAY